AI may have struck again with hallucinations. Yesterday evening, I was forwarded a quote from the case opinion of Shahid v. Esaam, 2025 Ga. App. LEXIS 299, at *3 [Ct App June 30, 2025, No. A25A0196]) released on June 30, 2025 by the Georgia Court of Appeals. (HT Mary Matuszak!)(link to official opinion, not Lexis):

We are troubled by the citation of bogus cases in the trial court’s order. As the reviewing court, we make no findings of fact as to how this impropriety occurred, observing only that the order purports to have been prepared by Husband’s attorney, Diana Lynch. We further note that Lynch had cited the two fictitious cases that made it into the trial court’s order in Husband’s response to the petition to reopen, and she cited additional fake cases both in that Response and in the Appellee’s Brief filed in this Court.

Background

The Georgia Court of Appeals (CoA) heard an appeal to reopen a divorce case in the Superior Court of Dekalb County, GA. The Appellant brought to the attention of the CoA that the “trial court relied on two fictitious cases in its order denying her petition.” The Appellee’s attorney ignored this claim and went on to argue the original argument of proper service by publication with multiple fictitious and misrepresented cases. The Appellee’s attorney also demanded attorney’s fees based on another fictitious case that claimed the exact opposite of existing case law. In total, the CoA provided this breakdown of the inaccuracy rate of the citations provided by the Appellant’s attorney, “73 percent of the 15 citations in the brief or 83 percent if the two bogus citations in the superior court’s opinion and the five additional bogus citations in Husband’s response to Wife’s petition to reopen Case are included.” The distraught CoA struck the lower court order, remanded the case, and sanctioned the Appellee’s attorney.

Digging into the Case

I was curious about all of this, so I did some digging this morning. I am still working on acquiring the CoA briefs, but I was able to access the documents from the trial court. The CoA was very cognizant that they do not have any actual proof at this time that AI was used, but with the number of bad citations that the Appellant’s attorney submitted, the CoA speculated about the use of a consumer AI model in the footnotes. To test this theory, I decided not only to do some reading, but to test out LawDroid’s new CiteCheck AI tool. Spoiler alert: I think the speculations are accurate.

CiteCheck AI

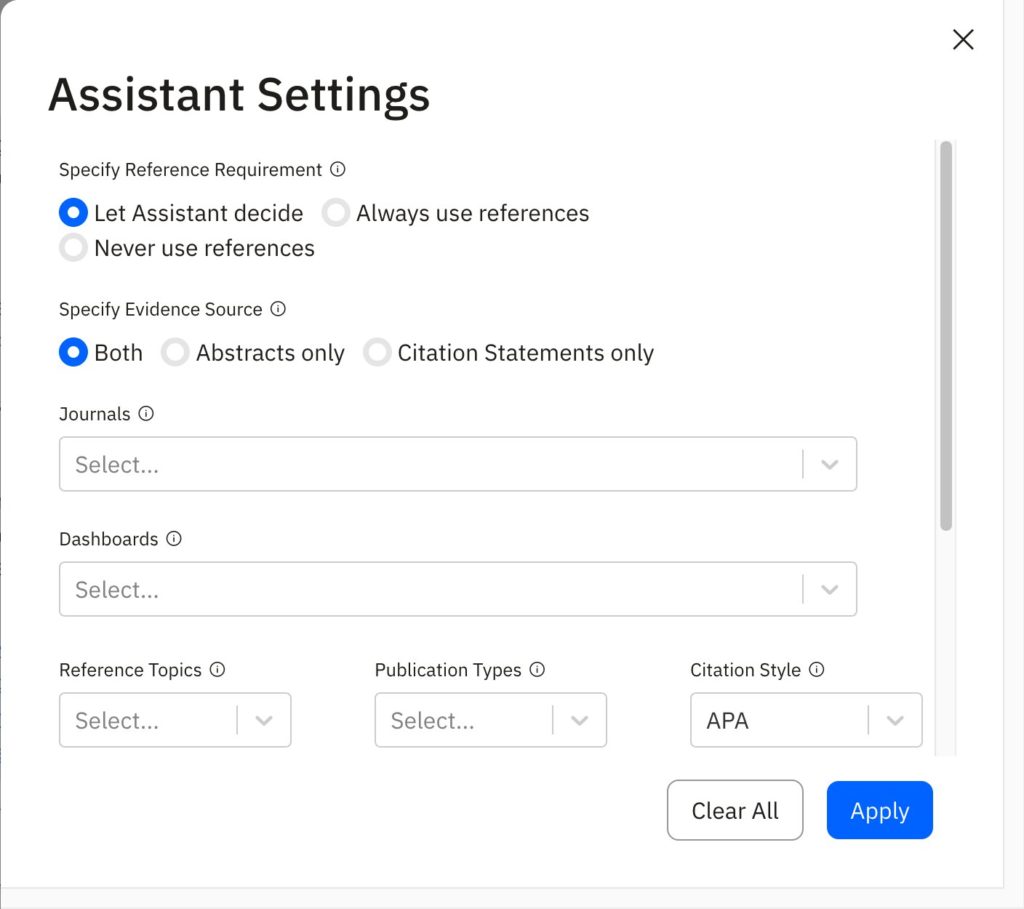

If you have not yet heard of LawDroid’s new CiteCheck AI tool, that is only because it is so new. The premise of this tool is you upload a document, and it will check your case citations to see if the citations exist (a.k.a. identify hallucinations). The free version gives you the ability to test it out with five documents. It will OCR your document (if needed), extract the citations, and check the citations against the CourtListener database. You are then given a nice table of the citations, marking them as valid or invalid. If the latter, you are also supplied the reason why it is marked invalid. Remember, however, this only checks their existence, not whether they stand for the proposition for which they are being used.

Bob Ambrogi posted a review of the application that he tested with the Mata v. Avianca, Inc.documents and a document he filed when in practice. From this review, I knew to expect a few false “invalid” markings if the case only has a Lexis or Westlaw citation or if there are abbreviation issues with the case citation. Bob noted that these issues were relatively easy to spot since CiteCheck AI lists the reason it marked the citation invalid.

The CiteCheck AI website also reminds attorneys that you still need to meet your ethical obligations and review everything before submitting it: “Disclaimer: CiteCheck AI is only a tool, it does not relieve lawyers from their duty of care, supervision, and competence. Ensure that you carefully review all work product before sharing it with clients and/or filing it in court.”

The Trial Order

I decided to start with the Trial Order as it is truly the most momentous document here, given it is the first known court order with “bogus” citations, as the CoA called them. The CoA specifically mentioned “the bogus Epps and Hodge case citations from the superior court’s order” in footnote 24, so I went in knowing what cases to watch out for. It turns out that these were the only two cases mentioned in the order, making them really easy to locate.

The first case was listed as “Epps v. Epps (248 Ga. 637,285 S.E.2d 180, 1981)” and was supposed to discuss service by publication. When I ran 248 Ga. 637 through Lexis, it led me to school financing case McDaniel v. Thomas, 248 Ga. 632, 632, 285 S.E.2d 156, 157 (1981) (note the different SE2d reporter citation!). Curious to see what the Epps parallel citation 285 S.E.2d 180 would lead me to, I found criminal case Lewis v. State, 248 Ga. 566, 566, 285 S.E.2d 179, 180 (1981). No sign of Epps v. Epps.

Next, I tried searching the parties. Epps v. Epps, restricted to Georgia cases, returned three results:

1. Epps v. Epps, 162 Ga. 126, 132 S.E. 644 (1926)(Sufficiency of the Evidence)

2. Epps v. Epps, 209 Ga. 643, 644, 75 S.E.2d 165, 167 (1953)(Implied Trusts)

3. Epps v. Epps, 141 Ga. App. 659, 659, 234 S.E.2d 140, 141 (1977)(Conversion)

None of the three discussed service by publication.

The second case was “Hodge v. Hodge (269 Ga. 604,501 S.E.2d 169, 1998),” another alleged service by publication case. Here is the breakdown of this case:

- 269 Ga. 604 led to fiduciary Atlanta Mkt. Ctr. Mgmt. Co. v. McLane, 269 Ga. 604, 503 S.E.2d 278 (1998)(agency, fiduciary obligations, and contracts)

- 501 S.E.2d 169 led to the middle of Foster v. City of Keyser, 202 W. Va. 1, 501 S.E.2d 165 (1997)(res ipsa loquitur)(Not even the same state!)

- Hodge v. Hodge search led to a divorce case! But no mention of service by publication in divorce: Hodge v. Hodge, 2017 Ga. Super. LEXIS 2178.

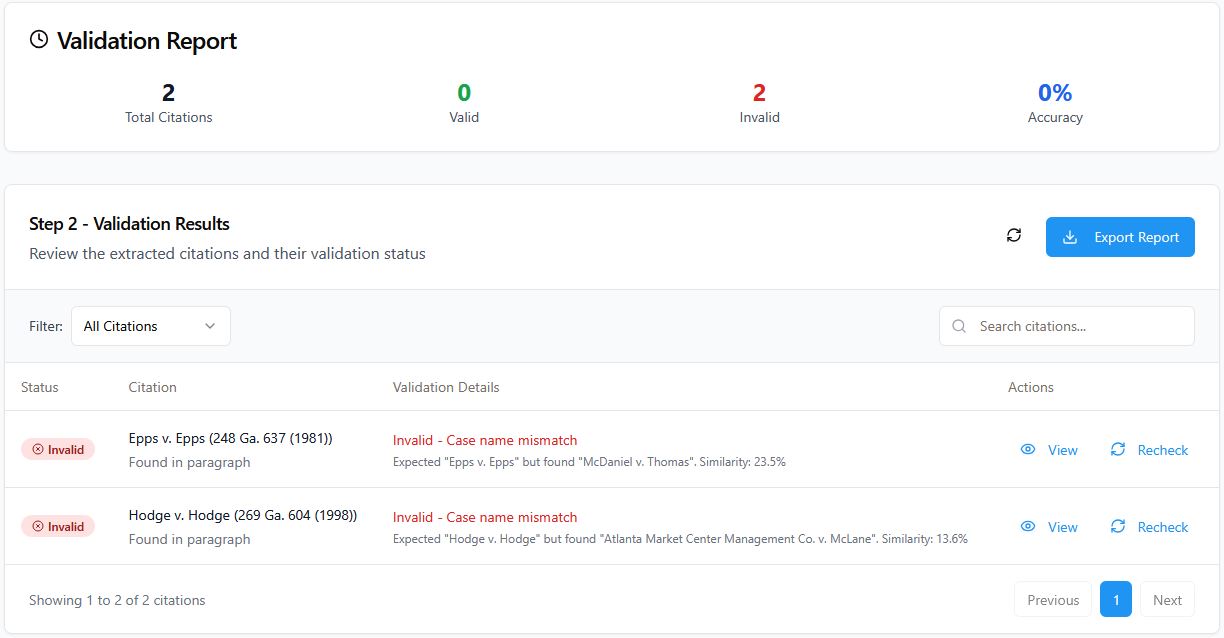

Trial Order – CiteCheck AI Review

Now that I have done the work by hand, how did Citecheck AI compare?

Success! We both found the same cases for the Georgia reporter cases. It did not check the parallel Southeastern Reporter citations, however. It definitely took a lot less time (under a minute) for CiteCheck AI than it did for me going through all four reporter citations in Lexis.

The Trial Response

Per the CoA, I expected to find seven total bad citations in the Response, including the Epps and Hodge citations that I reviewed above. Being a good (and nosy) librarian, I went through both the Georgia and the Southeastern Reporter citations for each citation, if provided. Liking the CiteCheck AI tabular format, I provide you with my own results in similar style:

| Case name | State Citation | State Result | Regional Reporter | Regional result |

| Fleming v. Floyd | 237 Ga. 76 | Campbell v. State, 237 Ga. 76, 226 S.E.2d 601 (1976) (criminal) | 226 SE2d 601 | Same case as Ga citation! |

| Christie v. Christie | 277 Ga. 27 | In re Kent, 277 Ga. 27, 585 S.E.2d 878 (2003)(attorney discipline) & In re Silver, 277 Ga. 27, 585 S.E.2d 879 (2003) (attorney reinstatement) | 586 SE2d 57 | Town of Register v. Fortner, 262 Ga. App. 507, 586 S.E.2d 54 (Ga. 2003)(summary judgment) |

| Mobley v. Murray County | 178 Ga App 320 | G. E. Credit Corp. v. Catalina Homes, 178 Ga. App. 319, 342 S.E.2d 734 (1986)(repossession) | 342 SE2d 780 | State v. Brown, 178 Ga. App. 307, 307, 342 S.E.2d 779 (Ga. App. 1986)(motion to suppress) |

| Robinson v. Robinson | 277 Ga. 75 | Robinson v. State, 277 Ga. 75, 586 S.E.2d 313 (2003)(criminal) | 586 SE2d 316 | Brochin v. Brochin, 277 Ga. 66, 586 S.E.2d 316 (Ga. 2003)(divorce decree finalized before attorney’s fees – no mention of service) |

| Reynolds v. Reynolds | 288 Ga App 688 | AT&T Corp. v. Prop. Tax Servs., 288 Ga. App. 679, 655 S.E.2d 295 (2007)(Tax) | N/A | |

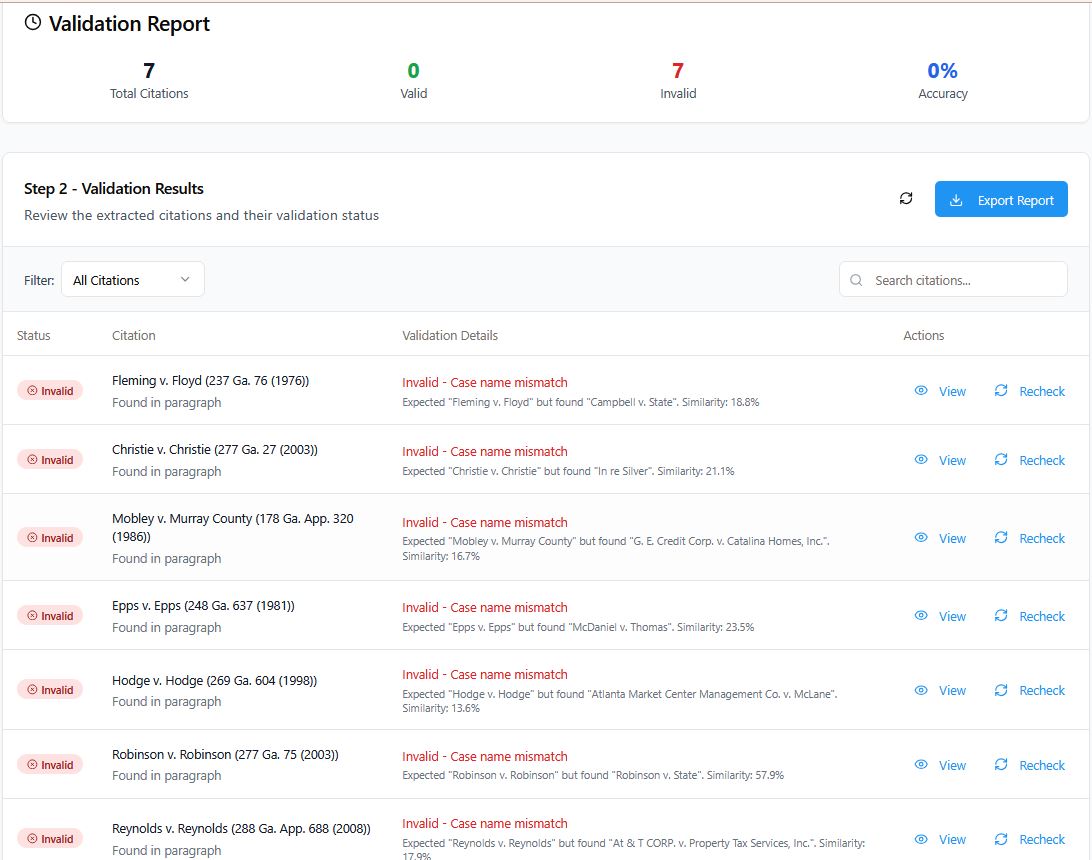

The Trial Response – CiteCheck AI Review

And success again! CiteCheck AI found the same cases that I did with a manual check for the Georgia reporter citations. Parallel citations once again were not considered, however (given the Bluebook no longer requires them, this may not be an issue for long). A new hiccup to take note of, however: It did not report that two cases were located with the Christie v. Christie Georgia reporter search. While page 27 is supposed to be the first page in the citation, it is not unheard of for a student or attorney to put the page number of the language they refer to instead. This makes me uneasy, and I hope this is on the improvement list to include both/all cases on the page listed.

Takeaways

From this exercise, I take a few key lessons and thoughts.

- The inevitable has happened, and a court has issued an opinion with hallucinated cases.

- The Court of Appeals did not investigate how the hallucinated citations were put into the order, but I am sure someone will. I await the final report.

- Give the disciplinary case that I read from the Christie v. Christie search, Georgia takes this sort of thing seriously. The Appellant attorney may face more than just sanctions in the future.

- The Citecheck AI tool is useful, as long as you remember its limitations.

- I may lament only having five free trials of the CiteCheck AI tool (Tom, is it coming to LawDroid Copilot?)

- I now fear the day another order is not caught and hallucinations become law.