Way back in 2023, I thought it was amazing how I could use generative AI to streamline my Thanksgiving prep: I gave it my recipes, and it gave me a schedule. It was a static list—a text document that told me when to put the turkey in, when to swap in the stuffing, and so on.

This year, I started with the same routine. I had six dishes—two stovetop, three oven, one “no-cook” dip—and a family who I’d promised dinner by 3:00 PM. I pasted the recipes into Gemini and asked for a timeline. It handled the “Oven Tetris” flawlessly, giving me a step-by-step game plan, with times and ingredient amounts at each stages.

But then, I had a realization: I didn’t just want an answer; I wanted a tool. I wanted to be able to check things off as I went. I wanted to see an overview and *also* zoom in on the details.

So, I asked: “What if this was a web app?”

The Shift: From Consumer to Builder

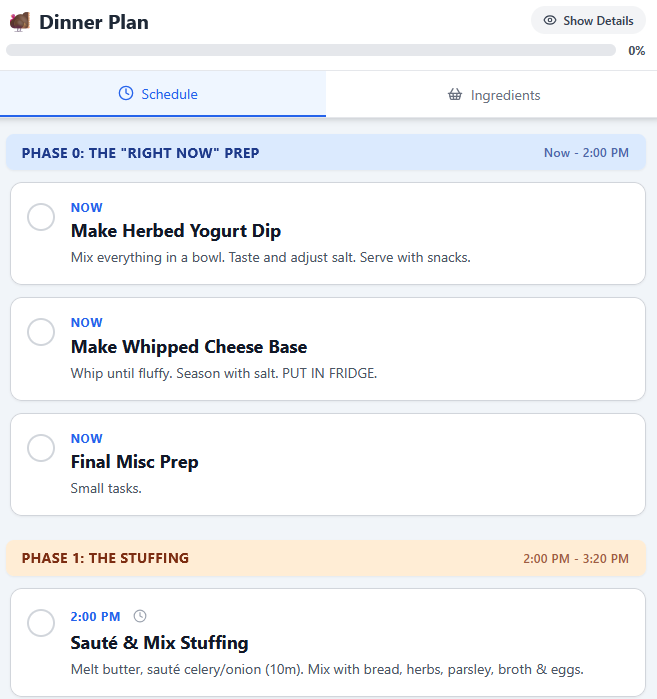

In seconds, Gemini went to work. It gave me a React-based interactive checklist. Suddenly, I wasn’t looking at a static timeline; I was interacting with a piece of software.

But the real magic happened when reality hit. As anyone who has managed a closing checklist or a trial docket knows, the timeline always slips. When my guests told me they’d be an hour late, I realized I’d have to manually calculate the drift for each step.

So, I issued a feature request (this is not a good prompt, but it didn’t matter):

“Add a feature where I adjust what time I’ve finished something so the rest will update”

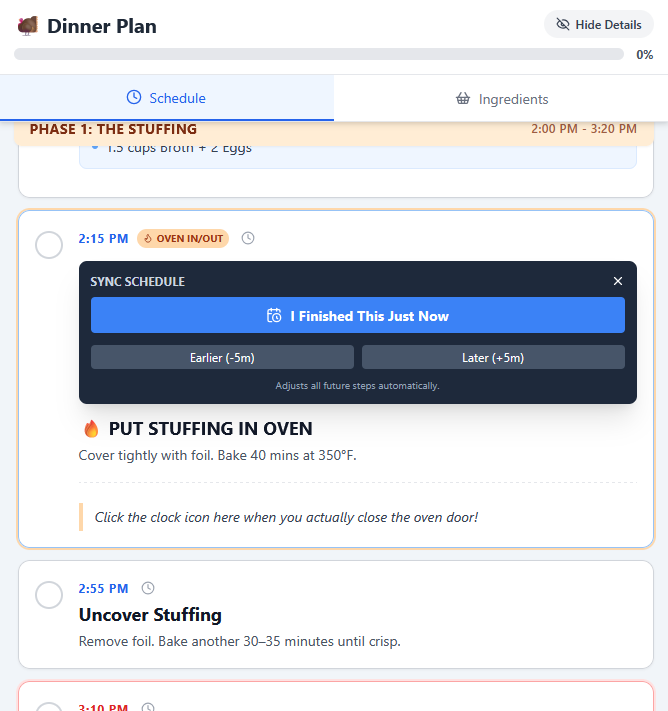

The AI updated the code. It added a little “reschedule” button, so when I tapped a clock icon next to “Stuffing In,” I could then tap “I Finished This Just Now,” and watch as the entire remaining schedule—the tart, the sprouts, the carrots—automatically shifted forward by an hour. Then I could do it again when I got my stuffing in later than the schedule called for. (If you’d like to check out my app you can do so here: Thanksgiving Checklist).

The result? Despite how tightly-timed my schedule was, dinner was on the table only 15 minutes late. For my household, where “at least an hour late” is the standard for a holiday meal, this was a massive victory.

The Era of “Single-Serving Software”

We often think of legal technology as big, enterprise-grade platforms: the Case Management System, the Deal Room, the Firm Portal. These tools are excellent for standard workflows. But legal work is rarely standard. It lives in the messy, human chaos between the formal deadlines.

My Thanksgiving experiment proves that the barrier to entry for building “Micro-Tools” has collapsed. We are entering the era of Single-Serving Legal Software—bespoke apps built for a single trial, a single deal, or a single crisis, and then discarded when the matter closes.

Here is what that looks like in practice (all ideas from Gemini because I’ve been out of legal practice too long… I’m curious if readers think any have merit):

1. Litigation: The “Witness Wrangler”

Standard case management software handles court deadlines, but it rarely handles the human logistics of a trial.

- The Problem: You have 15 witnesses. Some need flights, some need prep sessions, some are hostile. Their schedules depend entirely on when the previous witness finishes on the stand.

- The Single-Serving App: Instead of a static spreadsheet, you spin up a dynamic dashboard shared with the paralegal team.

- The “Reschedule” Feature: You click “Witness A ran long; pushed to tomorrow morning.” The app automatically text-alerts Witness B to stay at the hotel and updates the car service pickup time.

2. Transactional: The “Non-Standard” Closing

Deal software is amazing for corporate M&A, but terrible for “weird” assets.

- The Problem: You are selling a massive ranch. The closing checklist includes “Transfer Water Rights,” “Inspect Cattle,” and “Repair Barn Roof.” These aren’t just document signings; they are physical events with dependencies.

- The Single-Serving App: A logic-based checklist where “Cattle Inspection” is locked until “Barn Roof Repair” is marked Complete. If the roof crew is delayed, the inspection auto-reschedules, alerting all parties.

3. Mass Torts: The “Toxic Plume” Intake

Intake CRMs are generic. Sometimes the “qualification criteria” for a case are chemically or geographically complex.

- The Problem: You only want to sign clients who lived in a specific, jagged geographic zone between 1995 and 1998.

- The Single-Serving App: A simple web form where a potential client drops a pin on a map.

- The Logic: The app performs a “point-in-polygon” check against the specific toxic plume map you uploaded. It instantly tells the intake clerk “Qualified” or “Out of Zone,” saving hours of manual review.

The Accidental Product Roadmap

The beauty of this approach is that it requires zero commitment. I built this app for one dinner. I didn’t worry about making it generalizable. I didn’t build a “Recipe Importer” feature; I just hard-coded the stuffing because it was faster.

But now that I’ve used it, I’m thinking: “Next year, I should ask the AI to create a drag-and-drop interface so I can just paste URLs for any holiday.”

This is exactly how legal innovation should happen. Too often, firms try to buy or build the “Perfect Platform” first. It takes years and costs millions. Single-Serving Software acts as the ultimate Minimum Viable Product (MVP).

- Build a specific, hard-coded app for Jones v. Smith.

- Validate that the “Witness Rescheduler” actually saved the paralegal 10 hours.

- Generalize it only after it proves its value, so someone else in the firm can use it for Doe v. Roe.

You don’t start with the platform. You start with the problem.

A Note on Security & Tools

You might be thinking: “Wait, uploading client data to a web app? Compliance will have a heart attack.”

It’s a valid concern. But the beauty of these AI-generated tools is that they can often be delivered as a single HTML file that you can then save and run entirely locally on your machine—no data leaves the browser. Furthermore, if you are using an Enterprise version of your preferred LLM, your inputs remain within the firm’s secure boundary.

Speaking of tools, this capability isn’t exclusive to one platform. Whether you use Gemini, ChatGPT, or Claude, the ability to turn a prompt into a working React or HTML artifact is now a standard feature. The power lies not in the specific model, but in your willingness to ask for code instead of text.

Conclusion

We are no longer just the consumers of legal software; we are the architects. We can now build the infrastructure to manage our own chaos.

The next time you are drowning in a complex matter, don’t just ask AI for a memo or a checklist. Ask it for a tool. You might just find yourself managing the chaos (almost) on time.