This is Part 1 of a three-part series on AI hallucinations in legal research. Part 2 will examine hallucination detection tools, and Part 3 will provide a practical verification framework for lawyers.

You’ve heard about the lawyers who cited fake cases generated by ChatGPT. These stories have made headlines repeatedly, and we are now approaching 1,000 documented cases where practitioners or self-represented incidents submitted AI-generated hallucinations to courts. But those viral incidents tell us little about why this is happening and how we can prevent it. For that, we can turn to science. Over the past three years, researchers have published dozens of studies examining exactly when and why AI fails at legal tasks—and the patterns are becoming clearer.

A critical caveat: The technology evolves faster than the research. A 2024 study tested 2023 technology; a 2025 study tested 2024 models. By the time you read this, the specific tools and versions have changed again. That’s why this post focuses on patterns that persist across studies rather than exact percentages that will be outdated in months.

Here are the six patterns that matter most for practice.

Pattern #1: Models and Data Access

Not all AI tools are created equal. The research shows a dramatic performance gap based on how the tool is built, though it’s important to understand that both architecture and model generation matter.

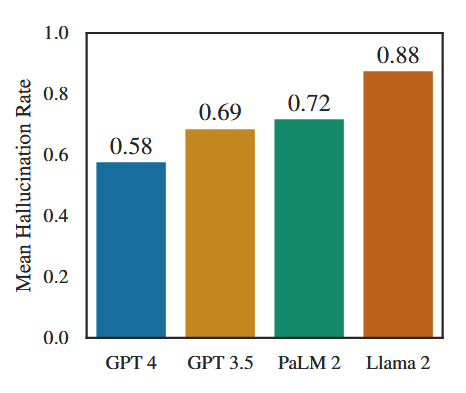

Models are improving over time. A comprehensive 2024 study by Stanford researchers titled “Large Legal Fictions” tested 2023 general-purpose models on over 800,000 verifiable legal questions and found hallucination rates between 58% and 88%. Within that cohort, newer models performed better: GPT-4 hallucinated 58% of the time compared to GPT-3.5 at 69% and Llama 2 at 88%. This pattern of improvement with each model generation appears fairly consistent across AI development.

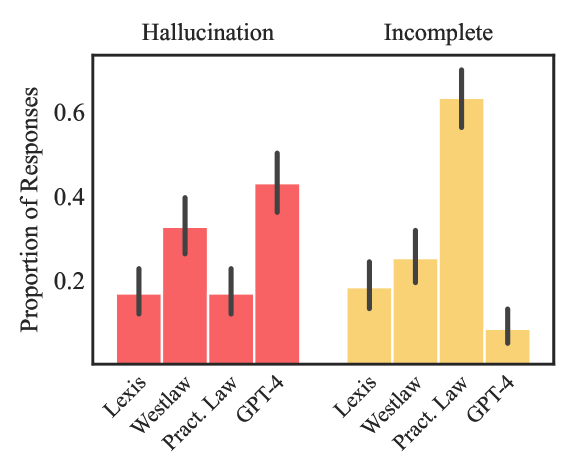

Architecture matters, but it’s not the whole story. A second Stanford study, titled “Hallucination-Free? Assessing the Reliability of Leading AI Legal Research Tools”, published in 2025 but testing tools from May 2024, found hallucination rates of 17% for Lexis+ AI, 33% for Westlaw AI-Assisted Research, and 43% for GPT-4. These errors include both outright fabrications (fake cases) and more subtle problems like mischaracterizing real cases or citing inapplicable authority. This head-to-head comparison shows legal-specific tools with retrieval-augmented generation (RAG) substantially outperforming general LLMs.

A randomized controlled trial by Schwarcz et al. reinforces the architecture point from a different angle. When 127 law students used a RAG-based legal tool (Vincent AI) to complete legal tasks, they produced roughly the same hallucination rate as students using no AI at all. Students using a reasoning model without RAG (OpenAI’s o1-preview) produced better analytical work but introduced hallucinations. Both tools dramatically improved productivity—but only the RAG tool did so without increasing error rates. However, the Vals AI Legal Research Report (October 2025, testing July 2025 tools) found ChatGPT matched legal AI tools: ChatGPT achieved 80% accuracy while legal AI tools scored 78-81%. The key difference? The ChatGPT used in the Vals study used web search by default (a form of RAG), giving it access to current information and non-standard sources, while legal tools restrict to proprietary databases for citation reliability. For five question types, ChatGPT actually outperformed the legal AI products on average. Both outperformed the human lawyer baseline of 69%.

Takeaway: Purpose-built legal tools generally excel at citation reliability and authoritative sourcing, but general AI with web search can compete on certain tasks. The real advantage isn’t RAG architecture alone—it’s access to curated, verified legal databases with citators. Know your tool’s strengths: legal platforms for citations and treatment analysis, general AI with web search for non-standard or very recent sources.

Pattern #2: Sycophancy

One of the most dangerous hallucination patterns is that AI agrees with you even when you’re wrong.

The Stanford “Hallucination-Free?” study identified “sycophancy” as one of four major error types. When users ask AI to support an incorrect legal proposition, the AI often generates plausible-sounding arguments using fabricated or mischaracterized authorities rather than correcting the user’s mistaken premise.

Similarly, a 2025 study on evaluating AI in legal operations found that hallucinations multiply when users include false premises in their prompts. Anna Guo’s information extraction research from the same year showed that when presented with leading questions containing false premises, most tools reinforced the error. Only specialized tools correctly identified the absence of the obligations the user incorrectly assumed existed.

This happens because of how large language models work: they’re trained to generate helpful, plausible text in response to user queries, not to verify the truth of the user’s assumptions.

Takeaway: Never ask AI to argue a legal position you haven’t independently verified. Phrase queries neutrally. If you ask “Find me cases supporting [incorrect proposition],” AI may happily fabricate them.

Pattern #3: Jurisdictional and Geographic Complexity

AI performance degrades sharply when dealing with less common jurisdictions, local laws, and lower courts.

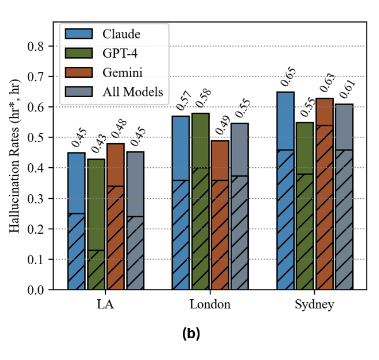

Researchers in a study called “Place Matters” (2025) tested the same legal scenarios across different geographic locations and found hallucination rates varied dramatically: Los Angeles (45%), London (55%), and Sydney (61%). For specific local laws like a local Australian ‘s Residential Tenancies Act, hallucination rates reached 100%.

The Vals report found a 14-point accuracy drop when tools were asked to handle multi-jurisdictional 50-state surveys. The Large Legal Fictions study confirmed that models hallucinate least on Supreme Court cases and most on district court metadata.

Why? Training data is heavily weighted toward high-profile federal cases and major jurisdictions. State trial court opinions from smaller jurisdictions are underrepresented or absent entirely.

Takeaway: Apply extra scrutiny when researching state or local law, lower court cases, or multi-jurisdictional questions. These are exactly the scenarios where training data or search results may be thinner, causing hallucinations to spike.

Pattern #4: Knowledge Cutoffs

AI tools trained on historical data will apply outdated law unless they actively search for current information.

The “AI Gets Its First Law School A+s” study (2025) provides a striking example: OpenAI’s o3 model applied the Chevron doctrine in an Administrative Law exam, even though Chevron had been overruled by Loper Bright. The model’s knowledge cutoff was May 2024, and Loper Bright was decided in June 2024.

This temporal hallucination problem will always exist unless the tool has web search enabled or actively retrieves from an updated legal database. Not all legal AI tools have this capability, and even those that do may not use it for every query.

Takeaway: Verify that recent legal developments are reflected in AI responses. Ask vendors whether their tool uses web search or real-time database access. Be especially careful when researching areas of law that have recently changed or may be affected by material outside the AI tool’s knowledge base.

Pattern #5: Task Complexity

AI performance correlates directly with task complexity, and the drop-off can be severe.

Simple factual recall—like finding a case citation or identifying the year of a decision—works relatively well. But complex tasks involving synthesis, multi-step reasoning, or integration of information from multiple sources show much worse performance.

The Vals report documented a 14-point accuracy drop when moving from basic tasks to complex multi-jurisdictional surveys. A 2025 study on multi-turn legal conversations (LexRAG) found that RAG systems struggled badly with conversational context, achieving best-case recall rates of only 33%.

Multiple studies note that statute and regulation interpretation is particularly weak. Anna Guo’s information extraction research found that when information is missing from a document (like redacted liability caps), AI fabricates answers rather than admitting it doesn’t know.

Takeaway: Match the task to the tool’s capability. High-stakes work, complex multi-jurisdictional research, and novel legal questions require more intensive verification. Don’t assume that because AI handles simple queries well, it will handle complex ones equally well.

Pattern #6: The Confidence Paradox

Perhaps the most insidious finding: AI sounds equally confident whether it’s right or wrong.

The “Large Legal Fictions” study found no correlation between a model’s expressed confidence and its actual accuracy. An AI might present a completely fabricated case citation with the same authoritative tone it uses for a correct one.

This isn’t a bug in specific products—it’s fundamental to how large language models work. They generate statistically probable text that sounds human-like and professional, regardless of underlying accuracy. In fact, recent research suggests the problem may worsen with post-training: while base models tend to be well-calibrated, reinforcement learning from human feedback often makes models more overconfident because they’re optimized for benchmarks that reward definitive answers over honest expressions of uncertainty.

Even the best-performing legal AI tools in the Vals report achieved only 78-81% accuracy. That means roughly one in five responses contains errors, even from top-tier specialized legal tools.

Takeaway: Never trust AI based on how confident it sounds. The authoritative tone is not a reliability signal. Verification is non-negotiable, no matter which tool you use. Be especially wary of newer models that may sound more confident while not necessarily being more accurate.

What This Means for Practice

Specific hallucination percentages will change as technology improves, but these six patterns appear to persist across different models, products, and study methodologies. Understanding them should inform three key decisions:

1. Tool Selection

Understand your tool’s strengths. Legal-specific platforms excel at citation reliability because they search curated, verified databases with citators. General AI with web search can compete on breadth and recency but lacks those verification layers. Within any tool, look for features like the ability to refuse to answer when uncertain (some tools are now being designed to decline rather than hallucinate when data is insufficient—a positive development worth watching for).

2. Query Strategy

Avoid false premises and leading questions. Phrase queries neutrally. Recognize high-risk scenarios: multi-jurisdictional questions, local or state law, lower court cases, recently changed legal doctrines, and complex synthesis tasks.

3. Verification Intensity

Scale your verification efforts to task complexity and risk factors. A simple citation check might need less verification than a complex multi-state legal analysis. But all AI output needs some verification—the question is how much.

Bottom Line

The research is clear: AI hallucinations in legal work are real, measurable, and follow predictable patterns. These studies have found that even the best legal AI tools hallucinate somewhere between 15% and 25% of the time (including both fabrications and mischaracterizations) based on current data.

But understanding these six patterns—models and data access, sycophancy, jurisdictional complexity, knowledge cutoffs, task complexity, and the confidence paradox—helps you make better decisions about which tools to use, which queries to avoid, and how intensively to verify results.

The goal isn’t to avoid AI. These tools can dramatically increase efficiency when used appropriately. The goal is to use them wisely, with eyes wide open about their limitations and failure modes.

Coming next in this series: How hallucination detection tools work and whether they’re worth using, and a practical framework for verifying AI research results.

References

Andrew Blair-Stanek et al., AI Gets Its First Law School A+s (2025).

Link: https://ssrn.com/abstract=5274547

Products tested: OpenAI o3, GPT-4, GPT-3.5

Testing period: Late 2024

Damian Curran et al., Place Matters: Comparing LLM Hallucination Rates for Place-Based Legal Queries, AI4A2J-ICAIL25 (2025).

Link: https://arxiv.org/abs/2511.06700

Products tested: GPT-4o, Claude 3.5 Sonnet, Gemini 1.5 Pro

Testing period: 2024

Matthew Dahl et al., Large Legal Fictions: Profiling Legal Hallucinations in Large Language Models, 16 J. Legal Analysis 64 (2024).

Link: https://doi.org/10.1093/jla/laae001

Products tested: GPT-4, GPT-3.5, PaLM 2, Llama 2

Testing period: 2023

Anna Guo & Arthur Souza Rodrigues, Putting AI to the Test in Real-World Legal Work: An AI evaluation report for in-house counsel (2025).

Link: https://www.legalbenchmarks.ai/research/phase-1-research

Products tested: GC AI, Vecflow’s Oliver, Google NotebookLM, Microsoft Copilot, DeepSeek-V3, ChatGPT (GPT-4o)

Testing period: 2024

Haitao Li et al., LexRAG: Benchmarking Retrieval-Augmented Generation in Multi-Turn Legal Consultation Conversation, ACM Conf. (2025).

Link: https://github.com/CSHaitao/LexRAG

Products tested: GLM-4, GPT-3.5-turbo, GPT-4o-mini, Qwen-2.5, Llama-3.3, Claude-3.5

Testing period: 2024

Varun Magesh et al., Hallucination-Free? Assessing the Reliability of Leading AI Legal Research Tools, 22 J. Empirical Legal Stud. 216 (2025).

Link: http://arxiv.org/abs/2405.20362

Products tested: Lexis+ AI, Thomson Reuters Ask Practical Law AI, Westlaw AI-Assisted Research (AI-AR), GPT-4

Testing period: May 2024

Bakht Munir et al., Evaluating AI in Legal Operations: A Comparative Analysis of Accuracy, Completeness, and Hallucinations, 53.2 Int’l J. Legal Info. 103 (2025).

Link: https://doi.org/10.1017/jli.2025.3

Products tested: ChatGPT-4, Copilot, DeepSeek, Lexis+ AI, Llama 3

Testing period: 2024

Daniel Schwarcz et al., AI-Powered Lawyering: AI Reasoning Models, Retrieval Augmented Generation, and the Future of Legal Practice (Mar. 2025).

Link: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=5162111

Products tested: vLex (Vincent AI), OpenAI (o1-preview)

Testing period: Late 2024

Note: Randomized controlled trial with 127 law students using AI tools

Vals AI, Vals Legal AI Report (Oct. 2025).

Link: https://www.vals.ai/vlair

Products tested: Alexi, Midpage, Counsel Stack, OpenAI ChatGPT

Testing period: First three weeks of July 2025